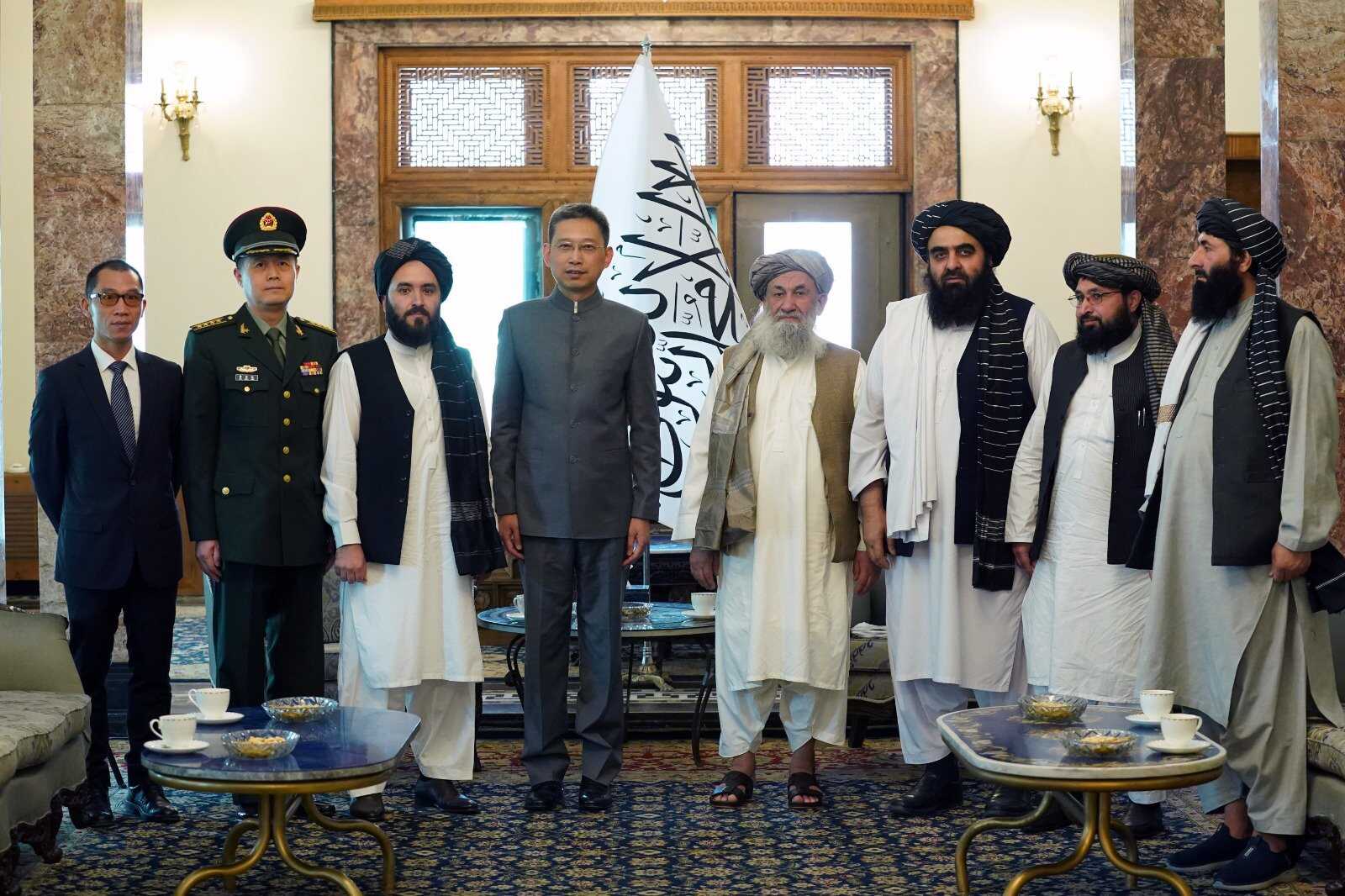

Whenever the human rights situation in the United States is questioned by others, the country's go-to response is first to admit they are not perfect, and then assert that their own problems do not land themselves in less of a position to criticize others. Interestingly, this more often works the other way around – criticism of others should by no means take away from one's own problems. In the same vein, when the United States and its allies bashed Iran and Afghanistan with criticism of women's rights at the latest session of the UN Human Rights Council, what women in the United States are calling for is more introspection.

Women across the country celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court ruling, which established abortion as a constitutional right, with more than 200 marches in 46 states. The 1973 Supreme Court ruling upheld individual liberty by recognizing that the decision whether to continue or discontinue a pregnancy belongs to the individual not the government. But that was overturned last year by a federal court decision under the auspices of a conservative-dominated bench. Such a decision caused an angry backlash among Americans, but abortion has nonetheless since been banned or severely restricted in 14 states. With such a regressive development, women find themselves denied their bodily autonomy and reproductive liberty.

Ironically, the striking down of the ruling cannot prevent abortion from taking place. In cases where abortion is criminalized, it more often than not leads to inappropriate abortion procedures and absence of post-abortion care, posing huge health risks to women aside from the erosion of their rights.

Sexual abuse is a salient and pervasive problem in the United States. The Me Too Movement, a broad-based social movement where women come out with their stories of surviving sexual abuse, also shocked the world with the magnitude of sexual assaults in the United States and how some stories had remained unspoken for up to decades. According to the American nonprofit anti-sexual assault organization Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), there are on average 463,634 victims of rape and sexual assault each year in the United States and millions of women in the country have experienced rape. In America, one in three women experience sexual violence in their lifetimes, according to the National Institutes of Health.

And reality may be even more gloomy, as those are likely underestimates given the inhibition of some victims to report and acknowledge traumatizing experiences that could invoke more pain or shame. And this is likely to be further compounded by the recent backslide in abortion rights.

Gender inequality also persists in the American workplace. The past 20 years failed to register any significant improvement in the gender gap in the United States. In 2022, women's earnings were on average 82 percent of what men earned, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis, looking at the median hourly earnings of both full- and part-time workers. This doesn't look that much different from the number in 2002, when women earned 80 percent of what men did. There also exists a gender promotion gap. A study by the MIT finds that female employees on average are 14 percent less likely to be promoted than their male counterparts, despite outperforming them and being less likely to quit. And the interplay between pay and promotion would leave American women in a more disadvantaged place than their male counterparts.

Such economics also contribute to the gendered-division of labor in American households. Lower wages for women are often cited as a crucial reason to remake working women into homemakers when there is a need to take care of the family and run the household without the budget to hire an extra hand. According to the Center for American Progress, when families cannot just live on one paycheck, "most working mothers return home to a second shift of unpaid housework and caregiving after their official workday ends. When paid work, household labor, and child care are combined, working mothers spend more time working than fathers." As a result, women bear disproportionate responsibilities for the family, while their personal and occupational space is acutely compressed.

Improvement in gender equity and in women's life takes more than critical narratives against other countries. What makes the life of women – and all people for that matter – better is reliable law enforcement, accountability, empowering policies and less stereotypical social expectations. In that respect, the United States can start with that at home.

Whenever the human rights situation in the United States is questioned by others, the country's go-to response is first to admit they are not perfect, and then assert that their own problems do not land themselves in less of a position to criticize others. Interestingly, this more often works the other way around – criticism of others should by no means take away from one's own problems. In the same vein, when the United States and its allies bashed Iran and Afghanistan with criticism of women's rights at the latest session of the UN Human Rights Council, what women in the United States are calling for is more introspection.

Women across the country celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court ruling, which established abortion as a constitutional right, with more than 200 marches in 46 states. The 1973 Supreme Court ruling upheld individual liberty by recognizing that the decision whether to continue or discontinue a pregnancy belongs to the individual not the government. But that was overturned last year by a federal court decision under the auspices of a conservative-dominated bench. Such a decision caused an angry backlash among Americans, but abortion has nonetheless since been banned or severely restricted in 14 states. With such a regressive development, women find themselves denied their bodily autonomy and reproductive liberty.

Ironically, the striking down of the ruling cannot prevent abortion from taking place. In cases where abortion is criminalized, it more often than not leads to inappropriate abortion procedures and absence of post-abortion care, posing huge health risks to women aside from the erosion of their rights.

Sexual abuse is a salient and pervasive problem in the United States. The Me Too Movement, a broad-based social movement where women come out with their stories of surviving sexual abuse, also shocked the world with the magnitude of sexual assaults in the United States and how some stories had remained unspoken for up to decades. According to the American nonprofit anti-sexual assault organization Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), there are on average 463,634 victims of rape and sexual assault each year in the United States and millions of women in the country have experienced rape. In America, one in three women experience sexual violence in their lifetimes, according to the National Institutes of Health.

And reality may be even more gloomy, as those are likely underestimates given the inhibition of some victims to report and acknowledge traumatizing experiences that could invoke more pain or shame. And this is likely to be further compounded by the recent backslide in abortion rights.

Gender inequality also persists in the American workplace. The past 20 years failed to register any significant improvement in the gender gap in the United States. In 2022, women's earnings were on average 82 percent of what men earned, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis, looking at the median hourly earnings of both full- and part-time workers. This doesn't look that much different from the number in 2002, when women earned 80 percent of what men did. There also exists a gender promotion gap. A study by the MIT finds that female employees on average are 14 percent less likely to be promoted than their male counterparts, despite outperforming them and being less likely to quit. And the interplay between pay and promotion would leave American women in a more disadvantaged place than their male counterparts.

Such economics also contribute to the gendered-division of labor in American households. Lower wages for women are often cited as a crucial reason to remake working women into homemakers when there is a need to take care of the family and run the household without the budget to hire an extra hand. According to the Center for American Progress, when families cannot just live on one paycheck, "most working mothers return home to a second shift of unpaid housework and caregiving after their official workday ends. When paid work, household labor, and child care are combined, working mothers spend more time working than fathers." As a result, women bear disproportionate responsibilities for the family, while their personal and occupational space is acutely compressed.

Improvement in gender equity and in women's life takes more than critical narratives against other countries. What makes the life of women – and all people for that matter – better is reliable law enforcement, accountability, empowering policies and less stereotypical social expectations. In that respect, the United States can start with that at home.